- Heddels

- Posts

- Oct 28 - Northampton History - Crown

Oct 28 - Northampton History - Crown

Nine Centuries of Shoemaking – The History of Northamptonshire

We take a look at the history of shoemaking in Northamptonshire, the beating heart of quality footwear in England's East Midlands.

James Smith

Northampton is the world capital of shoemaking. For nearly 1,000 years, the humble East Midlands town has been the epicenter of the craft, inspiring generations of British shoemakers to produce footwear of the highest quality.

From royal visits to navigating the Industrial Revolution, world wars, and more, Northampton, although not as buoyant as once was, remains the heartbeat of the world’s shoe industry. Today we’re looking at the history of Northamptonshire shoemaking in partnership with Crown Northampton, a fifth-generation shoemaker known for its end-tier, resoleable sneakers and boots.

Who is Crown Northampton?

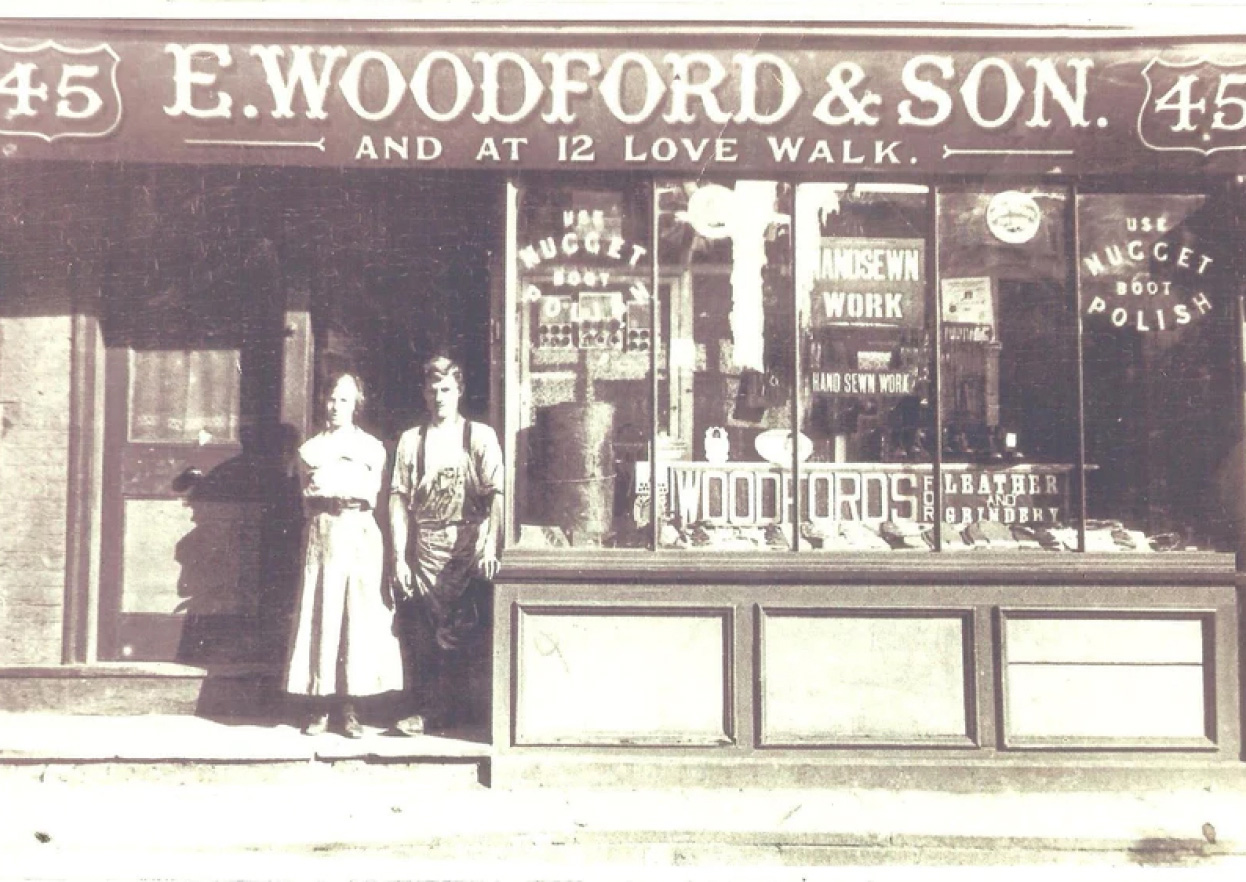

Crown Northampton is a British footwear brand intrinsically linked to century-old bespoke footwear maker, E. Woodford & Sons. Owned and operated by fifth-generation Woodford and shoemaker, Chris Woodford, Crown Northampton is known for its luxury sidewall stitched sneakers (dubbed the highest quality sneakers in the world by Rose Anvil’s Weston Kay) and stitchdown footwear, made to order in Northampton using the finest leathers and footwear components.

Crown Northampton’s DNA is centered on minimal sneakers designed by Chris Woodford. Unfussy and fine-tuned, each of Crown Northampton’s silhouettes focusses on understated elegance and structural perfection. Encapsulating this ethos is the newly released Everdon Rambler. Fusing smart-casual cool with the ruggedness of hiking footwear, the Everdon is one of the cleanest lug-soled ‘boots’ we’ve ever seen, perfect for weekend rambling and city trotting alike.

Crown Northampton Everdon Rambler, made to order for $565 from Crown Northampton.

12th Century Northamptonshire

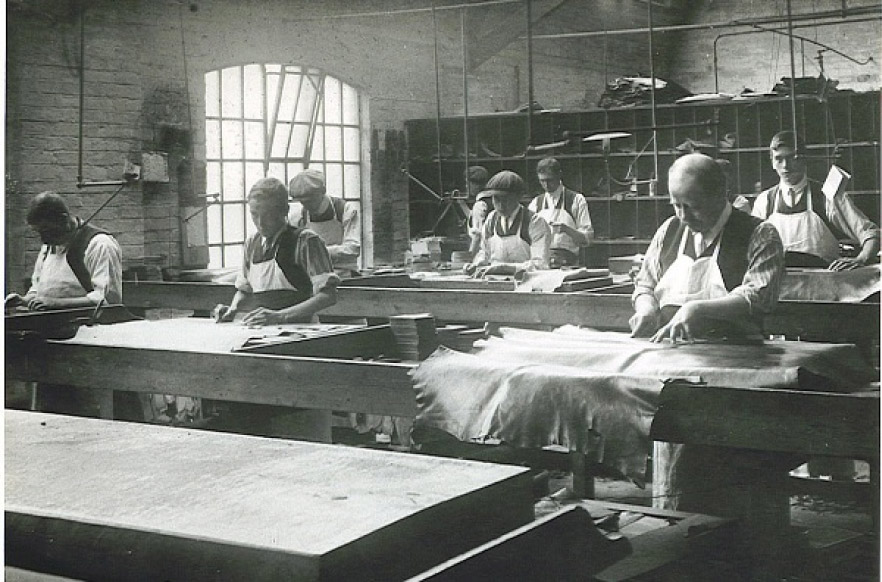

Early portrayals of shoemaking in England via E. Woodford & Sons.

Northamptonshire has a shoemaking history that reaches as far back as the 12th century. Northampton was a busy market town during this time, full of shoemakers (known as cordwainers), making bespoke footwear for locals. But this was nothing particularly unique — most towns had shoemakers — and Northampton was best known for its wool trade at the time.

What was special about Northampton was its tanneries, which used the healthy supply of oak bark from surrounding forests and water from the nearby River Nene to treat leather in their tanning processes. This proximity to leather suppliers led Northampton’s shoemaking population to grow into an omnipresent hub for merchants to sell locally made footwear.

Northampton also had the upper hand in terms of location, being easily reachable from London and on the route between Wales and London.

Royal Recognition

Northamptonshire also happened to be the home of Northampton castle, a property favored by King John, who ruled England from 1199 until his death in 1216. With Northamptonshire being one of the shoemaking hubs at the time, it is said that King John visited the market town in 1213 and purchased a pair of boots for 9 pence (roughly $40 in today’s money). The King was said to have been impressed by the quality of the footwear on offer, news which promoted other gentry and wealthy folk to check out Northampton’s shoemaking offerings.

King John via E. Woodford & Sons.

When King John passed away, his son, Henry III inherited the throne at just 9 years old (he wasn’t the last juvenile king of England, either). By his 20s, King Henry III was supposedly more admired than the tyrannical King John, a notion backed up by his charitable nature. For over 50 years, Henry III purchased footwear from Northampton to distribute to the poor during Christmas and Easter. This honorable policy also served to grow awareness of Northampton’s shoemaking prowess even further.

Shoemaking in England continued to grow over the next century. To protect the integrity and standards of the craft, the Guild of Shoemakers was founded in 1401. As well as the upkeep of quality shoemaking, the Guild served to establish workers’ rights and apprenticeship guidelines.

Military Contracts in Pre-Industrial England

A reproduction of the type of shoe produced in England in the 1600s

By 1600, boot and shoemaking was a thriving cottage industry in Northamptonshire, with a healthy population of outworkers (makers based in their own abodes). The first major mass-production outputs wouldn’t hit until around 1640. Entrepreneur Thomas Pendleton had been contracted by parliament to produce over 4,000 pieces of footwear for soldiers in Ireland.

Pendleton based his manufacturing operation in Northampton, using the town’s best shoemakers to fulfill the large-scale contract. Just 6 years later, another big contract arose, this time to supply footwear to Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army. Northampton wasn’t just a town of shoemakers anymore, it was the town of shoemaking.

Shoemaking illustration (left) and the type of boots worn during English Civil War (right)

By the early 18th century, Northampton was making most of the men’s footwear in England. Northampton-made shoes were worn by anyone from ordinary townsfolk all the way up to the wealthiest people in the land.

This is especially impressive in pre-industrial times, where shoes were still benchmade by one craftsman and their family, in the family home or workshop behind it. Numerous properties in Northamptonshire still have small outbuildings that would have been used to craft boots and shoes over 400 years ago.

Singer, Blake, and Factory Strife

Shoemaker’s Monday via E. Woodford & Sons

Before machinery, shoemakers used their crafting credentials to command respect. They were proud craftspeople who knew the importance of their profession. Shoemakers even introduced ‘Shoemaker’s Monday’, where they’d work from Tuesday to Sunday, get wasted, and take Monday off to recover and rest.

Illustration of the original Singer sewing machine first introduced in 1854 via E. Woodford & Sons

The Singer sewing machine arrived in the USA in 1850, invented in Boston by Isaac Singer. The Industrial Revolution had seen the introduction of other sewing machines — notably Elias Howe who had patent disputes with Singer — but Singer came out on top. Large shoe factories were established in Northampton in the late 1850s. This change marked a shift in clothing and footwear manufacturing, with many makers now based in factories or workshops as opposed to their homes. The cottage industry days were over, and the machine era was finally here.

Singer opened a factory in Glasgow in 1884 and began renting/leasing machines to craftspeople, making them more accessible than ever before. Machines could be 5x quicker than human hands, meaning the world of shoemaking had to embrace a new, modern way. Even the traditional, trailblazing shoemakers of Northampton.

1864 saw another new development in shoemaking – the Blake Sewer. Like the Singer, it was an American import, but unlike the Singer, it was a large piece of machinery, far more expensive, and needed steam power to run it. All of this made the Blake Sewer unsuitable for use in the home, making home-based shoemakers even less relevant. Many of them were disillusioned, feeling they had lost their autonomy and independence, forced to take up work in the larger factories.

A Northampton factory (left) and a Blake Sewer (right) via E. Woodford & Sons

Despite the somewhat exciting technological advancements, factory working proved to be a far cry from manufacturing at home or from your own workshop. Conditions were crowded, noisy, and unhealthy. Leather dust filled the air, which is a serious problem without proper ventilation. But perhaps above all else, factory work didn’t provide shoemakers — many of which were total artisans — the same level of satisfaction or control over their craft.

“You’d be trained on every part of the process but then assigned only to work on one stage. Each stage had distinct rooms for each part of production. Before, you might have done everything, now, workers were reduced to repeating one task over and over again.” -Rebecca Shawcross, senior shoe curator at Northampton Shoe Museum

Regardless of how the shoes were made, Northampton remained the hotspot for the best shoemakers in the land. Brands like Church’s, Edward Green & Co., Crockett and Jones, Tricker’s, Grenson, and Loake, all began operating in the 19th century and continue to make shoes to this day.

20th Century

A clicking room in Kettering, England, circa 1900

It wasn’t long into the 20th century that World War I erupted, generating a huge demand for military footwear. Of 70 million boots and shoes made for Britain’s WWI effort, up to two-thirds were produced in Northamptonshire. Despite the morbidity of the conflict, it boosted Northampton’s shoemaking economy beyond tenfold.

However, when the war ended in 1918, many of the men who were lucky enough to survive were unable or unwilling to make shoes. Many business owners or their would-be heirs had been killed, meaning numerous companies were shut down. Demand for men’s footwear that Northamptonshire specialized in understandably plummeted, meaning the shoemaking economy and employment suffered.

E. Woodford & Sons in London, early 20th century

Ernest Woodford — great-great-grandfather to Crown Northampton’s Chris Woodford — ran the family shoemaker E. Woodford & Sons in London throughout WWI after being sent home from the frontline. His son, Stanley, (Chris’ grandad) was primed to take over the company in 1939 but this was, of course, halted after the declaration of WWII.

Stanley was drafted into the army and survived WWII but spent many years suffering health complications as a result. His war diary, complete with hand-drawn maps and cartoons, sits in the Crown Northampton and E. Woodford showroom today, a reminder of the sacrifices made by people of the past for the present.

The advent of WWII meant that the shoemaking power of Northamptonshire was required once again. Similar numbers of boots and shoes were churned out by the craftspeople of Northampton, but when the war ended, Northamptonshire saw the same downturn in demand.

A pair of British Army Enlisted Man’s Boots from WWII, likely produced in Northampton, via Regimentals

To compound matters, manufacturing was being moved abroad to exploit labor. Droves of experienced shoemakers found themselves on the assembly line to make ends meet, utilizing less and less of their expertise and heritage skillset. During the 1950s many brands and factories were bought out by British financier Charles Clore, who shut them down and sent his contracts abroad to maximize profits.

Chancery Leatherwear factory via E. Woodford & Sons

But Northampton never dies. The 20th century saw more footwear brands arise in Northampton, like Dr. Marten’s (by way of the Northamptonshire-based R. Grigg) and Solovair. Stanley Woodford’s son, Andrew (Chris’s father) relocated to Northampton in the 1970s and began producing mocassins and cement-construction footwear under the name Chancery Leatherwear.

The Chancery operation grew quickly, largely owing to the abundance of skilled shoemakers in Northampton. Within just a few years, Andrew Woodford had 3 factories, over 250 staff, and an operation that produced over 100k pairs of shoes for department stores across the U.K. — a phenomenon that clearly illustrates the power of Northampton shoemaking.

Overseas Production Strikes Again

Despite its rapid success, Chancery Leatherwear wasn’t immune to the blight that hit British manufacturing in the 1980s. Mass production was beginning to be outsourced abroad, where goods were being made cheaply, and at a greater scale (albeit with far lower quality). Prices plunged, and smaller operations (in comparison to foreign megafactories) like Chancery were unable to compete. With most of his customers now sourcing footwear from Asia, Andrew closed Chancery Leatherwear in the mid-1980s.

It wasn’t just Chancery Leatherwear that suffered – much of Northampton’s shoemaking industry was decimated. Chancery was able to reinvent itself as a sports footwear manufacturer but this wasn’t the outcome for many other makers. Other legendary brands had to make sacrifices and cost-cutting exercises, including practices like outsourcing the bulk of production overseas and only finishing shoes in Northampton (see: Loake, Grenson). Church’s was sold to Prada in 1999.

Northampton & Crown Today

Chris Woodford of Crown Northampton

Despite fluctuating economic difficulties and the COVID-19 pandemic, Northampton remains the beating heart of the global shoemaking scene. It is synonymous with quality, and many of the world’s finest shoemakers have managed to retain 100% of their manufacturing in the East Midlands town.

Chris Woodford is one of the guiding lights in the Northampton scene, running Crown Northampton and E. Woodford & Sons with a passionate and mindful made-to-order business model that honors Northamptonshire shoemaking. Chris undertook an apprenticeship at Chancery Footwear and went on to study pattern cutting and design. He trained further by visiting industry veterans and returned to Chancery as a designer and shoemaker.

In 2005, Chris began designing his own range of footwear and traveled the world to understand his suppliers, the supply chain, and source the best possible materials. 11 years later, he founded Crown Northampton.

Fast forward to 2024, and Crown Northampton is one of the leading brands when it comes to made-to-order, resoleable, sidewall stitched leather sneakers. The made-to-order model cuts out wholesalers and distributors, meaning Chris is able to invest in top-tier materials that allow Crown Northampton to create a superior product.

“We don’t need to cover wholesalers’ percentages and all the other added costs that come with selling through distributors. That money saved means we can use the best materials and techniques at every stage of shoemaking and we can justify why our footwear is priced as it is.”

As well as crafting the best possible leather sneakers, Crown Northampton is committed to keeping the Northampton flame burning. Chris employs his former teacher, Len Robinson, to teach shoemaking skills to Crown Northampton staff.

Len is an industry veteran with encyclopedic knowledge of traditional construction methods. Many of the Crown workforce are 3rd-4th generation shoemakers, and those who aren’t are learning from the best.

Crown Northampton Harleston Derby, available at Crown Northampton from $535

Like this? Read these:

What did you think of today's newsletter? |